The Author Earnings team are attempting something unprecedented, and their work can’t be refined and improved unless there is some intelligent criticism of their findings.

This post is from 27 May 2015 and the trailblazing site it refers to, Author Earnings, is now sadly defunct. I have used Wayback Machine Archive links to show you what was there, where possible, because it’s still worth perusing – along with this excellent guest post. However, this post has not otherwise been updated except to clean up broken links. Comments remain open.

Today I’ve invited Phoenix Sullivan to blog on the topic. I’ve known Phoenix for a few years now, and if there’s a smarter person in publishing, I haven’t heard of them.

KBoards regulars will already know that Phoenix understands the inner workings of the Kindle Store better than anyone outside Amazon. And I can personally vouch for her expertise: she was the biggest influence on (and help with) Let’s Get Visible and also the marketing brains behind a box set I was in, which did very well indeed.

Phoenix offered to take the raw data from Author Earnings, drill down and analyse it, and then see if her conclusions differed from theirs, and whether there were any improvements she would suggest. Phoenix has also been able to pull some fascinating new insights from the Author Earnings raw data.

Here’s Phoenix with more:

Digging Deeper Into Author Earnings

I set aside some time recently to dive into the Author Earnings raw data for the May 1, 2015 Report. The irksome thing about the scraped data is how much of the puzzle that is Amazon’s ebook sales is missing and/or open to interpretative analysis. It isn’t the data’s fault or even the fault of the collection method. It’s simply that the data made public is limited, which in turn means a lot of creative interpretation goes into even so simple a task as coming up with the number of ebooks sold in a day. While the raw data itself isn’t changeable, different tools and assumptions applied to the data can yield different results, thereby opening up the analysis to differing interpretations.

My goal was to apply a set of tools and assumptions that update and possibly correct those being used by the Author Earnings team. The environment has changed dramatically in the 15 months since the first report came out, yet the analytical tools, in my opinion, haven’t necessarily kept up with the times. That in itself does not mean the results are wrong, but without a challenge to them, we’ll never know, right? Of course, even if the results are the same, there can be various ways to interpret those results, but we’ll get to that later.

Playing with someone else’s spreadsheet and formulas can be exhausting in itself. And time-consuming. Which is probably why there haven’t been many challenges to the essence of the AE data and analysis. My own methods for the challenge are likely cruder even than AE’s, and, like AE’s Data Guy, I’ve had to make certain assumptions along the way as well as do a little eyeballing and guesstimating.

Some bits, of course, are purely statistical and can be taken at face value. I’m not challenging the majority of the raw data, so my first assumptions are along the lines of:

- Ranks are correct.

- Publisher info is correct.

- Whether a title is in KU or not is correct, with the exception that several Amazon Imprint titles were not indicated to be in KU.

- An average 50% of KU downloads are sales; the other 50% are borrows.

- Authors at the Big 5 are, in general, earning 25% of actual net, not list, under the Agency model.

Assumptive corrections I’ve made include marking the four April Kindle First titles as having a sale price of $1.99 rather than $4.99. As the data was captured on the first of May, those Kindle First titles still in the Top 10 would have changed price around midnight and would owe their ranks to borrows and $1.99 sales. So other assumptions are:

- 10% of Kindle First titles are sales at $1.99, with normal royalties credited to the authors; 90% are borrows and are uncredited. For this exercise, that’s 12,000 borrows accounted for manually.

- For this exercise, I was forced to ignore the ghost borrow effect on rank, so the caveat is that most titles in KU are still being credited with more borrows and sales than they in fact have.

Sales-to-Rank Calculations

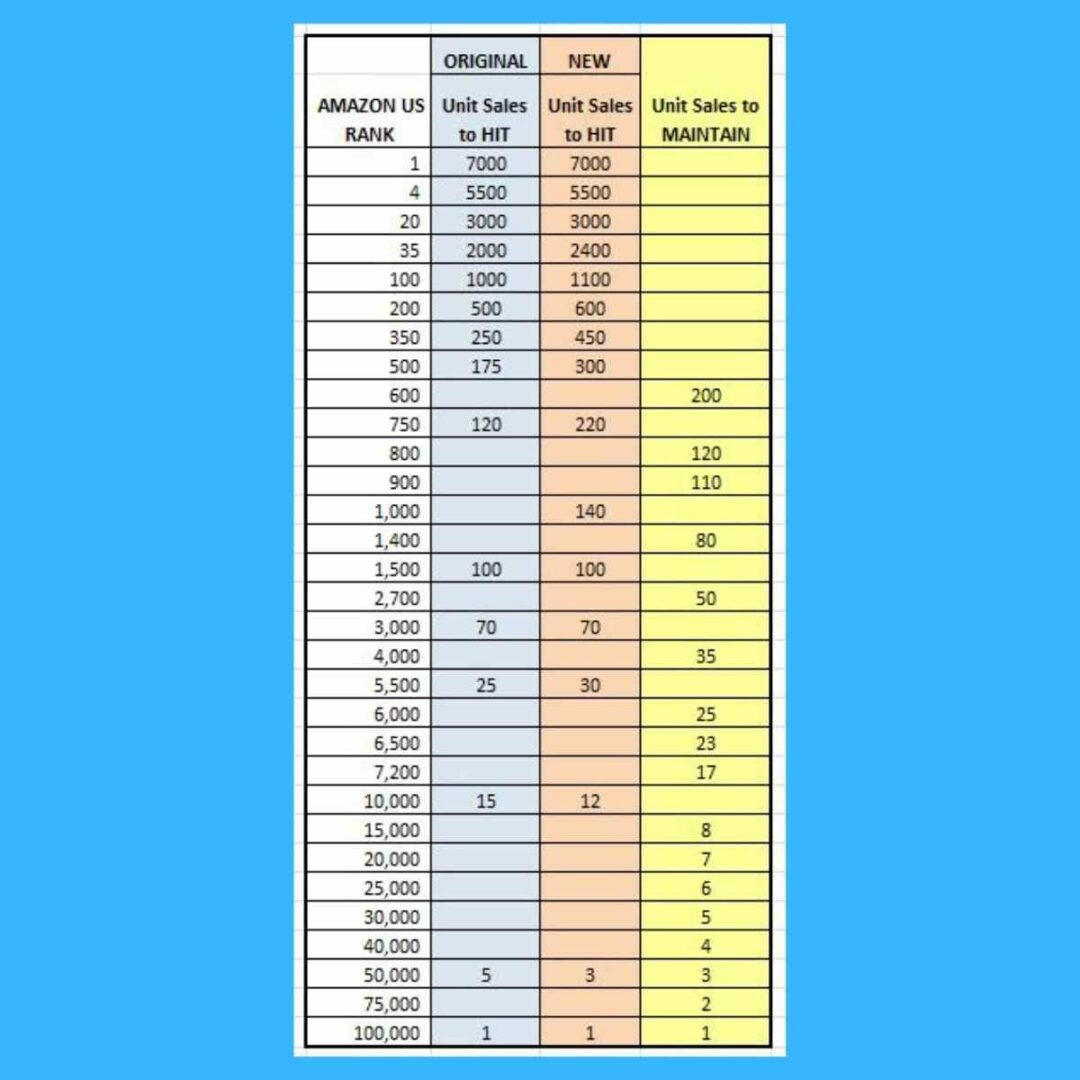

By far the biggest assumptive correction I’ve made is two-fold: The first part is applying a new set of sales-rank calculations to the dataset and the second part is applying calculations to maintain ranks rather than using the multipliers needed to hit a rank.

Let’s be clear that these multipliers are observed only, and best guesses across a lot of observations. However, I do believe the multipliers currently being used by AE are 1) outdated, and 2) don’t reflect the actual number of sales happening for the majority of books that are maintaining rank in the store and not seeing huge rank swings on a day-to-day basis.

I know the AE team is reluctant to introduce another variable into their quarter-to-quarter comparisons, but really this is pretty core to the reports. Not adjusting for sales numbers in a sales-based report is akin to not adjusting for currency exchange rates for companies doing business internationally. Especially when the discrepancy in earnings could be as much as a 25% deviation. Besides, KU’s thrown the whole sales-rank model askew already, so “consistency” really is no excuse here for not updating.

Compared to the rank chart AE is currently using, there’s about a 10% increase to hit #100 today and about a 50% increase to hit #1000. Closer to the #100,000 mark, there’s less of a deviation. While store volume is likely up, I highly doubt it’s up in the double digits, much less by 50%. What the increases are and where they’re occurring in the ranks indicates to me is that this is all part of the KU Effect and is more a product of ghost borrows (credit to Ed Robertson for the term) and converted borrows than of an increase in store volume. More titles are moving, true, but that volume movement isn’t all converting into earnings.

For a fun comparison, I applied the updated chart for the number of sales to hit a rank to see what that would look like. Predictably, it showed about a 7.7% increase in units sold and a 4.3% increase in total revenue from the original AE report for May 1, 2015.

However, Amazon’s algorithms take historical sales – among other variables, such as velocity – into consideration when calculating rank. The longer a title remains around a given rank, the fewer sales it takes to maintain that rank. Observably, anywhere from 10-50% fewer sales. That means the multipliers for hitting ranks are not good indicators of unit sales numbers for the majority of books in the dataset.

Here is my observed chart for average sales to maintain rank, along with the old and new numbers for hitting rank. More work needs to be done to fill in the upper brackets on the maintain side. I used the same numbers from my Sales to Hit chart when I felt I didn’t have enough data points on the Maintain side to chart new numbers in, but the safe assertion is that the Top 500 in my own data is over-reporting by a conservative 10%.

Plugging numbers from the maintenance chart into the calculation tool AE supplies in the raw data report better represents sales volume, I think. For the dataset, that means AE is reporting 17.4% more unit sales than what my calculations indicate (which, remember, are likely a bit high themselves), with the trickle-down effect of inflating the market as a whole. More on this later.

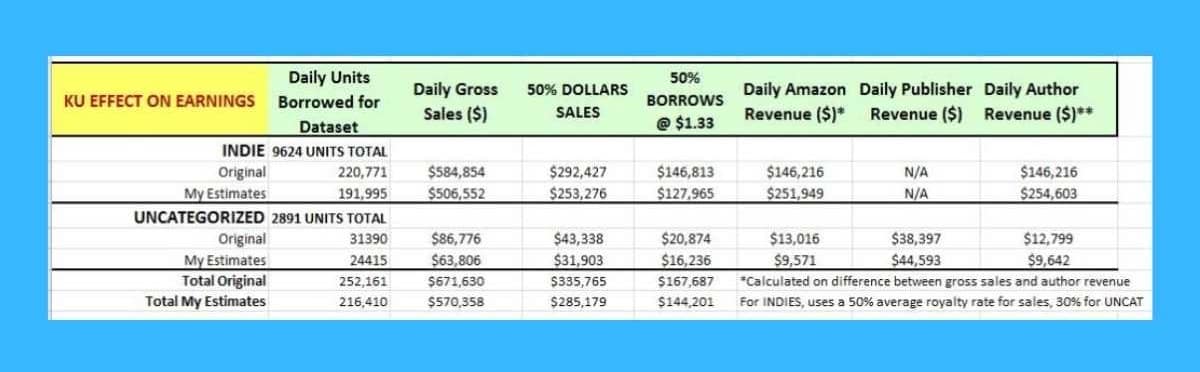

The KU Effect

Integrating KU into the reporting back in July dialed the difficulty of analyzing the data up into the stratosphere. Unread – and therefore unpaid – borrows influence rank across all titles. There’s no way to know how many borrows eventually become paid reads. And there’s no way to calculate how many units moved on any given title were at full price and how many were borrows, either paid or unpaid.

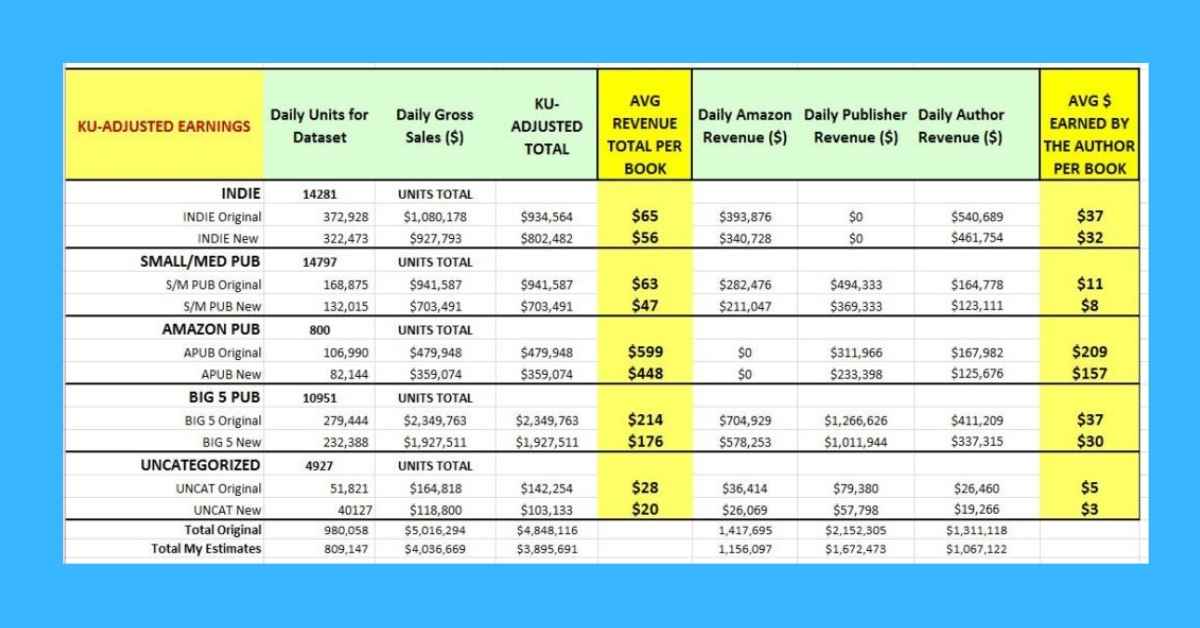

Self-reported numbers suggest the split of paid sales to paid borrows is about 50:50 (which still doesn’t account for the unread borrows that inflate rank), which is what the AE Reports use as well. Using the Maintain chart above, I rejiggered all the numbers. The adjusted royalties may well still be inflated, but are, I think, a closer approximation. The difference for the dataset is a statistically significant 21.4% spread in dollars (or the $400 million difference between $1.81 and $1.42 billion per year):

- $4,957,365 – original AE result for all earnings

- $4,848,116 – AE results with the new modeling applied

- $3,895,691 – my adjusted estimate

and for the KU amounts specifically:

- $167,687 – AE results for borrows with the new modeling applied

- $144,201 – my estimate

- 252,161 – AE estimate for total number of KU units sold/borrowed using the Maintain calculations for Indies + Uncategorized

- 216,410 – my estimate

For comparison, if we run the numbers against the KU payout information Amazon provides for the last 2 months, we get:

- Mar – $9.3M paid = $225,564 daily = 168,331 units @ $1.34

- Apr – $9.8M paid = $241,082 daily = 177,920 units @ $1.36

Amazon payout figures indicate a daily average of $233,323 and 173,125 units across the entire store inventory. We’re only looking directly at 46% of the Top 100K, though, in our dataset – which AE calculates as about 55% of gross. Adjusted, then, to 55%, those numbers become $128,327 and 95,218 units. We can’t extrapolate gross sales for both KU and non-KU from this, but we can extrapolate units moved at the assumed 50:50 ratio: 190,438 units.

Applying just the April payout figures (adjusted to 55%: $132,595 and 195,712 units), that’s about 21% less in dollars and 22% less in units than the AE Report indicates, and 8% less in dollars and 10% less in units than mine.

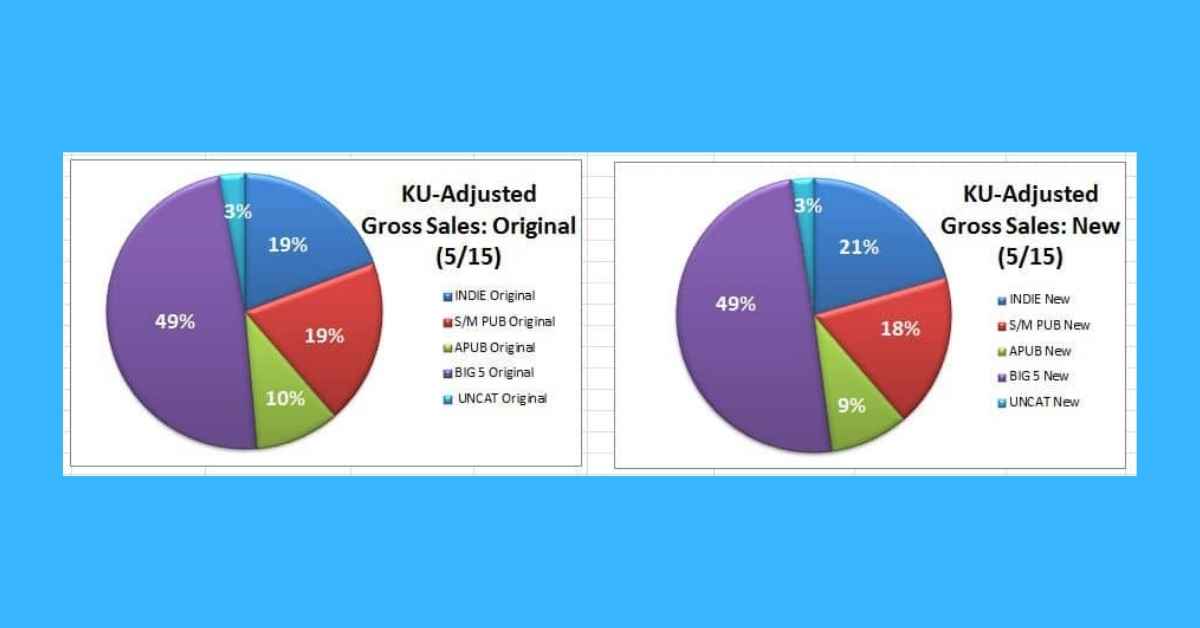

Average Totals Per Book & Author Earnings

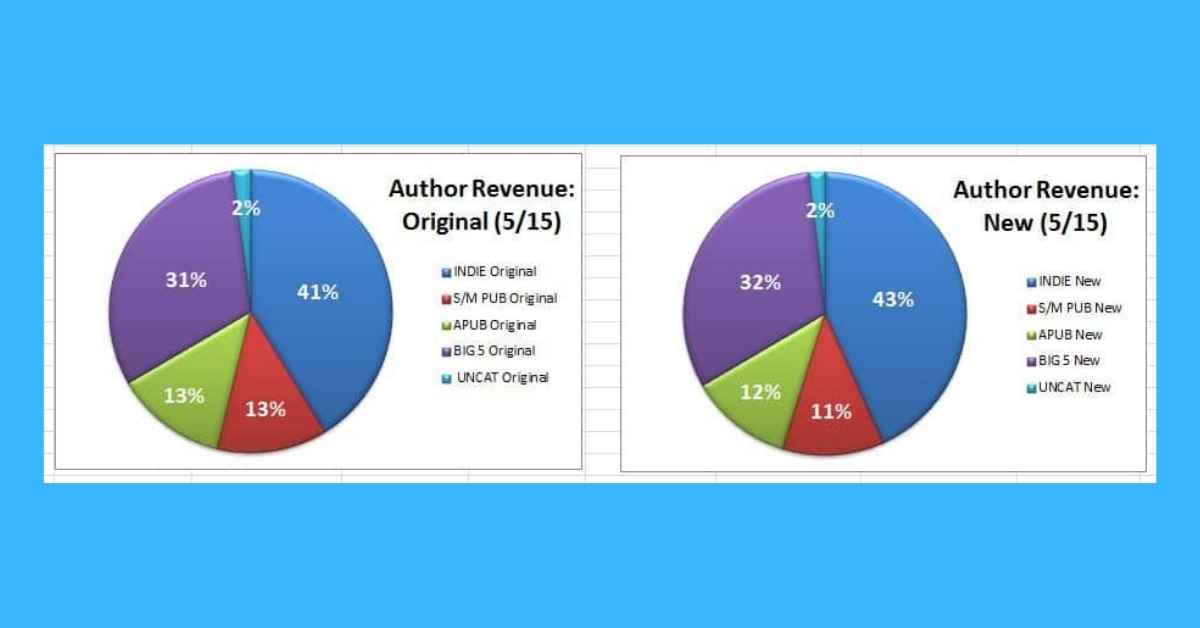

Since the AE Report looks at aggregated totals over individual sales and positions itself as one factor for authors to consider when deciding which path to publishing to pursue, I decided to see what each book averaged in each publishing path. There are pie charts below, but let’s also use words to be sure the picture is clear either way it’s expressed.

If we look at gross sales, we see that the Big 5 had only about 50% of the number of titles available in the dataset than indies had. Big 5 books sold about 78% of the number of books indies sold and made more than twice as much. A lot of that goes into Publisher and Amazon pockets, but what does that really mean?

The charts show that indie authors in aggregate earned about 25% more than Big 5 authors. In other words, it took almost 50% more available indie books to earn their authors 25% more than Big 5 authors. The chart doesn’t tell that whole tale on its own.

Actually, I’m not sure what purpose the Author Revenue pie chart serves despite the AE Report’s assurances that it’s these stats that mean more to us as authors. The trad industry doesn’t care. If it’s for authors for decision-making purposes, I think the earnings per title statistics are more telling. I calculated the same author revenue stats just for comparison sake, but really, as a savvy author, I find it kind of useless.

If we run a straight average, it’s easier to see how this plays out. Author earnings divided by total number of books sold = the average each book raked in. In the AE Report, indie authors and the Big 5 are tied in how much they make. In my estimate, indies actually make about 6.7% more. But Big 5 authors also have agents to pay! Yes, and indies have everything else to pay for. Meh.

Of course, looking at the above chart, it’s no contest how an author would want to be published on Amazon. Even using my less-kind-overall numbers, Amazon Publishing authors earn more per book than indies and the Big 5 combined, even after adjusting for Kindle First sales. And remember, APub has only 2% of the overall available titles.

The Big Picture

Challenge and Data Interpretation

How results are interpreted is generally as important as what data is captured and how it’s analyzed. This is why challenging the data and the analysis are important, and why it’s disappointing when the challenges aren’t made. Because challenge is how we learn – and how we affirm, as challenge doesn’t always mean disproving results.

Will I be doing more in-depth challenges? Probably not. It’s a lot of work and, to be honest, I don’t have the same agenda as the AE team. Or any agenda really. I only want to see a healthy marketplace for readers that I can sell into, in whatever form or model that takes.

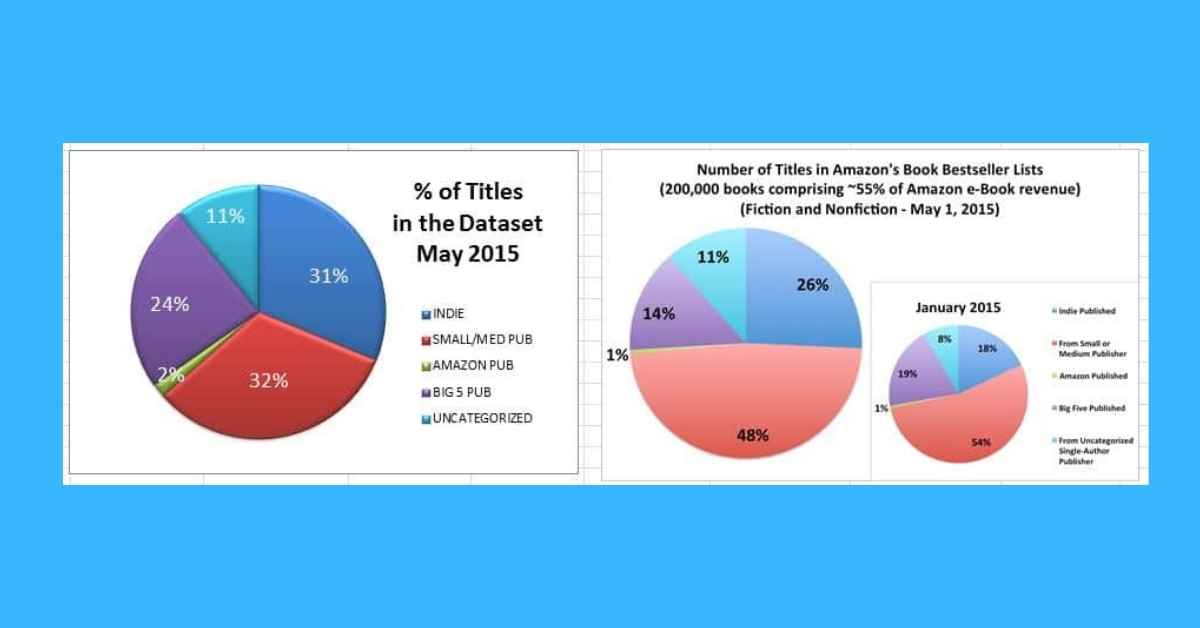

Big 5 Market Share Is Down – Or Is It?

The May AE Report looks at the effect of Agency Pricing by showing that fewer Big 5 books are in the Bestseller Lists (14% out of 200K titles) compared to January (19% out of 120K titles). The May Report also has more books in the May dataset. When I looked at the dataset I pulled from the report (the Top 100K), I found that the 14% increased to 24%. Of course, when we put numbers to those percentages and extrapolate the results, we find:

- May 2015 AR Report: 14% of 200K =28000

- Jan 2015 AR Report: 19% of 120K = 22800; extrapolated, that’s 38,000 titles in the Top 200K

That seems like it could be in line, but if we try that with 24% of the 100K, we get a whopping 48,000 extrapolated.

I did go back and look at the percentages across the Top 50K, 25K and 10K to see if Big 5 bestsellers were swarming more towards the higher/better ranks. At each tier, the number of Big 5 titles was down from the January report about 5% while the number of indie titles were up 5%.

Was this due to an increase in KU titles, perhaps, with ranks inflated via ghost borrows? No. When I ran the totals there, the number of KU titles at each tier in January ranged 46.9% to 47.3%, while for May the range was 42.9% to 44.4%.

Even so, using my methodology and adjustments for KU, I calculated the Big 5 market share of gross sales at 49%.

The main thing percentages don’t tell us, though, are the true dollar figures. If we compare AE’s Jan and May 2015 reported numbers, we see (for the same Top 100K):

- $4.6M Total Gross Sales Jan

- $4.97M May

- $877,782 Total Indies Sales Jan

- $1,080,178 May

- $2,336,912 Total Big 5 Sales Jan

- $2,349,763 May

Market Share

From the above, we can say that while market share may have eroded for the Big 5, gross sales plateau’d between Jan and May. Losing market share is not the same as bleeding money. Besides, the ebook market – discrete from the general publishing market – is relatively new.

The Big 5 were never part of that market until it became lucrative enough to play in, and only once indies were invited into the market did it start to burgeon. Not because of indies, but the timing is inseparable. Big 5 never dominated the market, and a few deviation points here and there doesn’t mean it’s losing the market.

And while percentage charts are pretty to look at, they don’t always describe an accurate picture. Ebooks, for instance, have lured a certain percentage of customers away from the used-books market. The Big 5 were not in the used-book market before and their models don’t include that market now.

Ebooks for the Big 5 are a segment, a department, a subsection of the overall publishing market that only those producing the ebooks cares about. Ebook departments are likely given a target goal: Sell $100 million in gross and increase your profit margins by 2% in 2015, for example. The goal isn’t necessarily chasing market share as is so narrowly defined in the AE Reports.

More helpful is knowing how much the market is expanding and then seeing what effect that expanded market has on wallet share. If I’m a Big 5 corp putting out the same number of titles per year in a market that grew 5% in the past year because billionaire werewolves were suddenly hot and my bread-and-butter is nonfiction and nongenre, my goal is likely not to capture that part of the market I don’t cater to. So losing 1% in those market conditions can still be an overall gain for the company.

If Big 5 goals are to preserve print, then we can’t determine anything about agency pricing’s success or failure looking only at ebook stats. If ebook sales are flat but print sales are up, then I would consider that a success for the Big 5. Print sales could be floundering right now for all I know, but the point is that I don’t know, so I cannot draw any sort of conclusion from the data in front of me other than that Big 5 gross sales plateau’d while its market share slipped a couple of percent. On Amazon. In the US.

Likewise, if indies in the aggregate gain a 10% share in a market that’s overall grown by 4% but the average number of dollars going into each indie’s individual pocket is down 3% because 10,000 new indies have entered the market, then how should that be reported? It, of course, depends on the agenda the reporting entity subscribes to. If it’s trads vs indies, then aggregate reporting that doesn’t care about the individual supports the indie win.

Do indies care how much marketshare indies in the aggregate have in an expanding – or contracting – market? Does a thriller writer gauge the health of their business by what the nonfiction segment or the romance genre is doing? Do they look at the overall expanding market in thrillers and set goals to dominate or do they see where they’ve reached a plateau and expand into other segments such as print, foreign and audio to compete before turning to other tactics, such as price drops, to increase ebook sales?

Market analyst reports are great for observing behavior at a macro level that only businesses, such as Amazon and BN, who have a finger in each granular slice of the pie can truly appreciate. Looking at the yin of lost publisher profits in the last quarter without looking at the yang of whether publisher profits have increased in other segments such as print only tells part of the story. Making sweeping generalizations of the elephantine publishing industry based on looking at the general health of the elephant’s four legs in aggregate and ignoring the rest of the beast is about as accurate as ignoring valid changes in the ecosystems being analyzed and not correcting for them.

Or basing the decline of BN store volume off a single data point.

Personally I would love to see third-party industry leaders do some rigorous challenges to the conclusions being drawn. I’m not saying the AE team’s conclusions are necessarily wrong. Just that a lot of folk are taking a lot on faith – and I remain a skeptic.

Takeaways:

- Raw data is neutral – it is neither wrong nor right; it”s what”s not there and has to be filled in along with what tools and assumptions are used to look at the data that can lead to different interpretations of what the data means.

- It”s perhaps time to update the tools being used to analyze the raw data since the metrics and the ecosystem have both undergone major upheavals since the analyses began.

- Actual dollar and unit amounts tell a part of the publishing story that using percentages only to express the data doesn”t necessarily address.

- More challenges to the data analysis and the conclusions – both AE”s and mine – are needed to validate them.

About Phoenix Sullivan

Phoenix is the Managing Director of Steel Magnolia Press, a micro-publisher/indie author consortium that has sold over 1.5 million ebooks. She is mostly looking forward to retiring later this year. Although the last time she tried retiring from the corporate world, Steel Magnolia was the result…